Sharing Some of the Sunshine that Marcel Proust Spreads Through Swann’s Way, In Search of Lost Time Volume 1

I heard of the French author Marcel Proust for the first time in the compassionate visionary Alain De Botton’s book the School of Life: An Emotional Education. In the chapter The Importance of Sex, Botton talks about Marcel Proust’s lesbian sex scene from his book Swann’s Way. Proust’s Swann’s Way is the volume one of his influential seven-volume collection In Search of Lost Time.

In the scene, the lover Mademoiselle Vinteuil invokes her partner to spit on the photo of her deceased father. This heavily criticized section describes how Vinteuil is just trying on the freedom of sensual pleasures — which may make her appear wicked. The author Proust argues that despite what one might think, Vinteuil is essentially of a moral and sound character.

Proust writes, “Sadists of Mlle Vinteuil’s kind are beings who are so purely sentimental, so naturally virtuous that, for them, even sensual pleasure seems evil, seems the privilege of the wicked. And when they allow themselves to indulge in it for a moment, it’s the wicked whose skin they try, and try to get their accomplice, to enter into, so as to have had the momentary illusion of escaping their scrupulous and gentle soul in the inhuman world of pleasure.”

Swann’s Way (and I’m sure the following six volumes) are full of such long (really long and semi-coloneated) lines full of deep wisdom about human composition, our inherently corrupt and compassionate nature, the everlasting misery of love and desire, and the sweetness of life. The writing is so ingenious I wonder why don’t I run into Proust’s work more often. After all, a plethora of articles, textbooks, reviews, essays, and biographies draw on Proust’s grandiose contributions to literature, including How Proust Can Change Your Life by Alain De Botton (which I will read soon). But in today’s world of ever-fleeting focus, we shouldn’t be surprised that titles as heavy, long, complex, and volumed as Proust Swann’s Way (and In Search of Lost Time books) have been run over by Instagram and Tik-Tok.

No matter how late to the party, I feel fortunate to finally discover Proust in all his abundant vulnerability, passion, tenderness, anxiety, and vigor. I’ve benefited from his writing and understanding of human emotions as much as I have gained from Rabindranath Tagore (Gora specifically) and Leo Tolstoy (Anna Karenina), and now the three join hands as my teachers on human complexities and realistic writing. (These two are part of the list of books that changed how I think about life.)

Though I shouldn’t be too joyous because I have only read the first volume. Before succumbing to pneumonia at the age of 51 (suffering from asthma throughout his life and maybe having severe anxiety of getting separated from his mother), Proust had left behind seven heavy volumes of his memorable novel In Search of Lost Time, originally called “A la recherche du temps perdu”, and at a point, “Remembrance of Things Past.” And irrespective of how much joy and learning I’ve found from this volume, I’m scared to pick up the subsequent pieces. (But I won’t be surprised if I’m to be found pouring through them soon enough.)

It is with moroseness I say, that my notes below are only from Section 1 and Section 2 of Swann’s Way – In Search of Lost Time Volume 1. So we are merely talking about 180 pages out of the 490 (as my Kindle states). Truth be told, if I have to share the brilliant sentences from the entire book, I may have to start another blog dedicated to the one and only Proust. (Not a bad idea, huh?) So I will, for now, be gratified with this piece on Proust’s profound insight into humans and the other one of his quotes I shared above.

Hope you devour these wholesome grains of wisdom as vigorously as I did.

Enjoy.

43 Moments of Genius, Compassion, and Human Understanding From Marcel Proust (In Search of Lost Time, previously known as Remembrance of Things Past)

#1

“But even as it relates to the most insignificant things of human life, we are not a materially constituted whole, identical to everyone and which a person need only come to know, like an account book or a will; our social personality is created by what others think.

#2

“Even this very simple act we call “seeing a person we know” is in part an intellectual act. We fill the physical appearance of the being we’re seeing with all of our notions about him, and in the more complete picture we form of him, these notions predominate. They succeed at inflating his cheeks so perfectly, at adhering to the line of his nose so faithfully, at coalescing with his voice, in all its nuances, so seamlessly (as though his voice were but a transparent envelope), that each time we see this face, hear this voice, it’s these notions we’re encountering.”

#3

“But my grandmother, she, in any weather, even when the rain was pounding and Françoise had to quickly bring in the precious wicker chairs so they not get ruined, could be seen out in the empty, hail-whipped garden, pushing back her disorderly grey hair so her forehead could better imbibe the benefits of the wind and rain. She said, “Finally, a person can breathe!” and went up and down the soaked paths — arranged too symmetrically, she believed, by this new gardener who didn’t have a sense for nature and whom my father had been asking all day if the weather would improve — with enthusiastic and irregular little steps which expressed the various shifts her soul was undergoing amid the intoxication of the storm, the power of physical well-being, the stupidity of my education and the symmetry of gardens: and not a desire, unknown to her, to guard her plum-colored skirt against mud stains, under which the garment disappeared, to the distress and despair of her maid.”

#4

“My grandmother went back outside, sad and discouraged, but cheery nonetheless, for she had such a soft and humble heart that her affection for others and the little attention she paid to her own person and her own sufferings crystallized in her eyes in a smile where, unlike what we see in so many human faces, there was no irony, save for herself, and which, for all of us, was like a kiss, for her eyes couldn’t see a person she cherished without passionately caressing them.”

#5

“Each time she saw another to possess an advantage, however slight, that she herself didn’t have, she persuaded herself that it wasn’t an advantage at all, but a misfortune, and she pitied them so as not to have to envy them.”

#6

“But the only one among us for whom Swann’s coming became the object of a painful obsession was myself. This was because on nights where strangers — or only M. Swann — came to the home, Momma didn’t come up to my bedroom. I dined before everyone else and afterwards stayed at the table until eight o’clock, the set time at which I went upstairs; this precious and fragile kiss Momma ordinarily conferred to me as I lay in bed, at the moment before I was to enter sleep, I was forced to transport it from the kitchen to my bedroom and keep it the whole while I undressed, without shattering its tenderness, without letting its volatile virtue scatter and evaporate; and on these very nights where I had to receive it in the most cautious manner, I was forced to seize it in public, abruptly steal it, without even the necessary time and freedom to bring to what I was doing the attention of the maniac who forces himself to think of nothing else while closing the door so that when his pathological incertitude returns to him he can victoriously oppose it with his memory of this action.”

#7

“Perhaps he more than anyone would have been able to understand me; for him, this anxiety at feeling that the person we love is in a merry atmosphere where we are absent, where we can’t go to meet up with her, it was love that had acquainted him with it, the love that is in a way predestined to monopolize it and specially adapt to it; but when, as in my case, this anxiety has entered into us before love has made any appearance in our life, it floats, awaiting its apparition, vague and free, without a fixed attachment, to service a certain sentiment one day and a different one the next, sometimes filial affection, sometimes friendship.”

#8

“I was increasing my agitation in trying, by force of will, to calm myself by accepting my misfortune.”

#9

“But also, since he didn’t have principles (in my grandmother’s sense of the word), he, properly speaking, was neither flexible nor inflexible.”

#10

(Speaking of his father) “When he sent me to bed, merited the name less than did the severity my mother and my grandmother exercised on me, for due to his nature, which in certain respects differed from mine more than theirs did, he probably hadn’t guessed just how unhappy I was every night, something my mother and my grandmother, on the contrary, knew very well; but they loved me enough not to consent to sparing me this suffering they wanted to teach me to overmaster so as to decrease my nervousness and strengthen my will. As for my father, whose affection for me was of a different kind, whether he would have had this courage I’m unsure: for as soon as he realized that I was feeling sad, he said to my mother, “Go and console him.””

#11

““But Madame, why is Monsieur crying like that?”, my mother responded, “He doesn’t know himself, Françoise, it’s his nerves; make up the other bed for me and then go to bed yourself.” For the first time, my sadness wasn’t considered a punishable offence, but was an illness I couldn’t control and which was being officially recognized, was a nervous state I wasn’t responsible for; I was given the relief of not having any misgivings mixed into my bitter tears; I could cry without sin.”

#12

“I should have been happy; I wasn’t. It seemed to me that my mother had made her first great concession for me, one that must have been very painful for her, that it was her first abdication before the ideal she had conceived for me, and that for the first time she, as courageous as she was, had admitted defeat. It seemed to me that if I had won a victory it was against her, that I had succeeded, like an illness, like sorrows or like old age could have, in relaxing her will, in bending her judgement; I felt that this night was the beginning of a new era and would always be a sad date.

Her anger would have been less sad for me than this new tenderness which I had never known in my childhood; it seemed to me that I had, with an impious, secretive hand, come to trace the first wrinkle on her soul, had given her her first grey hair.”

#13

“In her life too, when it wasn’t works of art but other people that had inspired her affection or her admiration, it was touching to see all the deference with which she banished from her voice, from her gestures, her words, any sign of gaiety that might have caused pain to some mother who in her past had lost a child, any reference to a birthday or an anniversary that might have brought some elderly gentleman to think of his advanced age, any talk of household things that might have appeared tedious to some young scholar.”

#14

“A delicious pleasure had invaded me, in isolation, without there being any notion of its cause. In the same instant it made me indifferent to all of life’s tribulations, made its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory, operating in the same way as love in filling me with a precious essence: or, rather, this essence wasn’t in me but was me. I no longer felt mediocre, contingent, mortal. But where could this powerful joy have come from? I felt that it was connected to the taste of the tea and the cake but infinitely exceeded it, was not of the same nature.”

#15

“What did it signify? Where could I apprehend it? I drink a second mouthful which gives me nothing more than first, a third which gives me a little less than the second. It’s time that I stop, the virtue of this drink seems to be diminishing. It’s clear that the truth I’m seeking isn’t in the drink: it’s in me. The tea had awakened this truth but didn’t know it; it could only indefinitely repeat, with less and less force each time, this same testimony, which I wasn’t able to interpret and which I wanted at least to be able to call upon again shortly and find intact, at my disposal, so as to attain a decisive explanation: I put down the cup and turn to my thoughts. They alone could find the truth. But how?”

#16

“And she disappeared, embarrassed that someone like my mother should concern herself over her, perhaps so that no one see her cry; Momma was the first person to give her this tender emotion of feeling that her life as a peasant, her joys, her sorrows could be of interest, could be a cause of happiness or sadness for someone other than herself.

#17

“She was one of these household servants who are at once most displeasing, at first impression, to a stranger, perhaps because they don’t go to the effort of winning him over or don’t show him enough attention, knowing very well that they have no need for him, that he’ll never again be received into the home, and who are, on the contrary, most highly esteemed by those among their masters who have tested their real capacities and don’t care about this superficial cordiality, this servile chatter that makes a favourable impression on a visitor but often conceals an unteachable stupidity.”

#18

“And my thoughts, were they not themselves like a crèche, another one, in the depths of which I remained plunged, even when I was seeing what was going on outside? When I saw an exterior object, my awareness that I was seeing it stayed between it and myself.”

#19

“The novelist’s great discovery was in having the idea to replace these impenetrable parts of the soul with a like quantity of immaterial contents, that is things our soul can incorporate into itself. What does it matter whether or not the actions, the emotions of this new genre of beings appear to us as true, when we’ve made them our own, when it’s in us that they’re being produced, when they’re regulating, as we feverishly turn the pages, the rapidity of our breathing and the intensity of our gaze.”

#20

“And once the novelist has put us in this state of mind where, like in all purely interior states, all emotion is heightened, where his book disturbs us in the way a dream does, but a dream that is more clear than those we have when sleeping and our memories of which are more enduring, all at once he unleashes in us, in the span of an hour, every possible joy and sorrow, some of which, in life, take years to come to know, and the most intense of which remain hidden from us because the nature of their slow development prevents us from perceiving them (so changes, in life, our heart, and it’s the greatest sorrow; we can only come to know of it through reading, through imagining: in reality it changes, like certain phenomena produced by nature, so slowly that, if we’re able to note each of its different states in succession, conversely, the feeling of passing through a change is lost on us).”

#21

“They resolved, in the end, that the tears my grandmother’s indisposition had brought to his eyes weren’t feigned: but they knew by instinct or by experience that our surges of emotion have little bearing on the rest of our actions and on the way we conduct our lives, and that respect for moral obligations, loyalty to one’s friends, proper execution of a task, keeping resolutions, found a surer foundation in blind habits than in ardent and ultimately barren momentary transports.”

#22

“One of these passages of his, the third or fourth that I isolated from the rest, gave me a joy that was incomparable to that which I had derived from the first, a joy that I sensed was felt in a deeper region of myself, somewhere more united, more vast, and from which all obstacles and partitions seemed to have been lifted.”

#23

“If his daughter said, in her thick voice, how happy she was to have seen us, not an instant after it seemed that inside of her a sister more sensible than she was blushing at this dumb schoolboy remark that might have made us think she was imploring us to invite her to our home.”

#24

“I couldn’t thank my father; he got annoyed by what he called sentimentality.”

#25

“But when nothing is left of an ancient past, and after all beings have died, after everything has been destroyed, more fragile but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, scent and taste remain, and will for much time yet, like souls, to recall, to wait, to hope in the ruins of all else, to carry, undistorted, in their nearly intangible droplet, the immense edifice of memory.”

#26

“In a sort of rapturous dream, he smiled, then he went back towards the lady, hurrying, and, as he was walking faster than usual, his two shoulders oscillated from left to right in a ridiculous manner; and so fully had he, in caring nothing for anything else, abandoned himself to his happiness that he looked as though he were the sentiment’s inert and mechanical puppet.”

#27

“He couldn’t, at least by his own volition, know that he was a snob, since all we can ever know are others’ passions, and what we come to know about our own we learn only through our neighbours.”

#28

“When he passed by us, he didn’t stop speaking to her, but he, from the corner of his blue eye, made a little sign to us which, if you will, began and ended within his eyelids and which, not involving the muscles of his face, could pass perfectly unnoticed by his conversation partner; but looking to, through the intensity of the sentiment, compensate for the slightly narrow field to which its expression was confined, he made the azure corner of his eye which had been assigned to us sparkle with all the enthusiasm of a cordiality that exceeded cheerfulness and bordered on mischief; he refined the delicacies of amiability into winks of connivance, hints, innuendos, mysteries of complicity, and finally exalted his assurances of friendship into manifestations of tenderness, into a declaration of love, illuminating, with a secret languor that was for us alone and was invisible to the lady with the country house, an enamoured pupil in a icy countenance.”

#29

“Legrandin’s snobbery, as such, had never advised him to pay frequent visits to a duchess: it set Legrandin’s imagination to making this duchess appear adorned with every grace. Legrandin got on closer terms with her, imagining he was yielding to this attraction based on another’s intellectual qualities and virtuous character and of which the vile snobs are ignorant. It was only others who knew he was a snob; for, in their inability to understand the intermediary action of the imagination, they saw Legrandin’s social activity and its primary cause side by side.”

#30

“All of a sudden I stopped, I could no longer move, as what occurs when a vision is addressed not only to our sight but calls on our deeper perceptions and has our entire being at its disposal.”

#31

“And so it was that through the Guermantes Way I learnt to distinguish these states that succeeded one other in me at certain moments, and that had the effect of dividing each day, the one coming to chase away the other with the punctuality of a fever; contiguous, but each so exterior to, so devoid of means of communication with the other that I could no longer understand, nor even picture to myself, in the one state what I had desired or dreaded or accomplished in the other.”

#32

“I was all the more disposed to believing this (and to believing that the caresses through which she would introduce me to this foreign taste would also be of a particular kind and would contain such pleasures as I couldn’t have known through anyone but her) for I was still — and would be for years to come — at this age where one has yet to isolate the pleasure of possessing a woman from the different women with whom one has experienced it, where one has not reduced it to a general notion that has us consider them — women, on the whole — as interchangeable instruments for an always identical pleasure.” [I believe we can read the whole sentence with woman/women replaced by man/men]

#33

“And it was in this same moment — thanks to a peasant who was passing by, in a sour mood that was only exasperated when he nearly got hit in the face with my umbrella, and who responded without warmth to my “lovely weather, isn’t it, a great day for a walk!” — that I learnt that the same emotions aren’t simultaneously inspired in every being at any given moment.”

#34

“Facts don’t penetrate into the world of our beliefs; they didn’t engender these beliefs and don’t destroy them; they can oppose them with the most tireless contradictions without weakening them, and an avalanche of sorrows or illnesses befalling a family won’t bring them to doubt the charity of their god or the talent of their doctor.”

#35

“But for a man like M. Vinteuil, he, more than others, must have suffered intensely in his resignation to one of these situations people wrongfully believe are exclusive to bohemian society: they arise every time a vice needs to establish itself with all the space and security it requires, a vice that was cultivated in the child by nature alone, sometimes merely through blending the virtues of his father and mother, in the same way as it dictates the colour of his eyes.”

#36

“This tendency to try to rise up to their level, which is an almost mechanical response to every disgrace we suffer.”

#37

“She searched as far off from her true moral nature as she could to locate the language befitting the vicious girl she wished she was; but the words she could imagine such a girl saying in earnest, on her own lips seemed false.”

#38

“But, beyond its physical expression, in Mlle Vinteuil’s heart, wickedness, at least at first, surely was not unamalgamated. Sadists like Mlle Vinteuil are the artists of their wickedness, something wholly wicked persons couldn’t be. The latter, since their wickedness isn’t outside of them, they regard it as perfectly natural, they aren’t able to distinguish themselves from it;”

#39

“It wasn’t that her wickedness gave her her notions on pleasure, that this wickedness seemed attractive to her, it was that pleasure seemed evil. And as each time that she gave herself over to this pleasure it was accompanied by wicked thoughts that were otherwise absent from her virtuous soul, she finished with finding this pleasure diabolical, with identifying it with evil.”

#40

“Perhaps she wouldn’t have thought of wickedness as being so rare, so extraordinary, so exotic a state, one so relaxing to emigrate to, had she known how to discern in herself, as in everyone else, this indifference to the sufferings one causes, which, whatever different names we give it, is cruelty’s terrible and permanent form.”

#41

“He slurred his words when he spoke and this had an adorable effect, as one felt that it betrayed less a speech impediment than a mark of the soul, a remnant of the innocence of childhood that he had never lost.”

#42

“Deep down, she admired “her lady,” whom she judged as superior to all these people since she didn’t want to receive them. In short, what my aunt required of a person was that they at once approve of her regimen, pity her for her suffering and reassure her of her future.”

#43

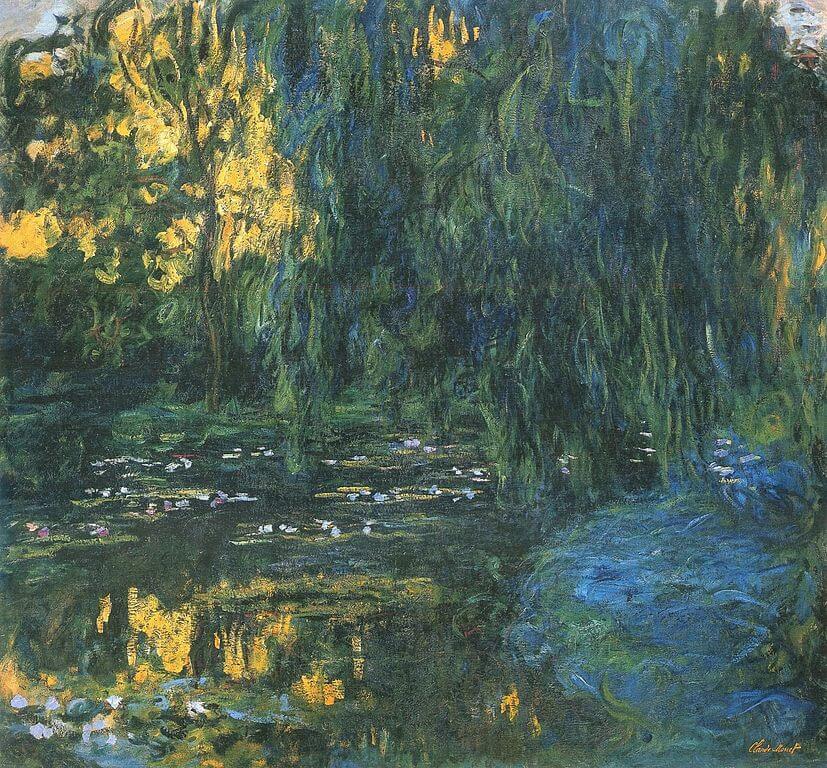

“And yet, because there is something individual in places, when I’m seized with the desire to see the Guermantes Way again, it wouldn’t be satisfied by someone bringing me to a river path where you saw waterlilies that were just as beautiful or even more beautiful than the ones in the Vivonne, no more than I would have, in the evening, at coming home — at the hour where I felt this anxiety that later emigrates into love and may become forever inseparable from it — wanted a mother more beautiful and more intelligent than mine to come say goodnight to me.”

“But for this same reason, and in so much as they continue to exist in these present-day impressions of mine to which they might bind, they give them a foundation, a depth, a further dimension than the others. Also, they add a charm, a meaning to them that is for me alone.”

Onwards we go.

Follow Up Read: 42 Quotes From Proust’s In Search of Lost Time

Which one of these beautiful paragraphs from Remembrance of Things Past by Marcel Proust did you like the most? Tell me in the comments.

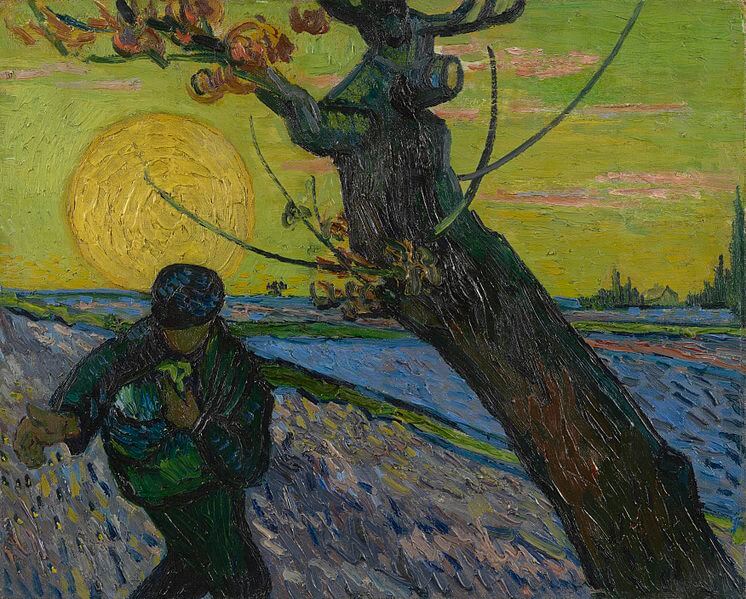

Feature Image Courtesy: Édouard Vuillard, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

*****

My much-awaited travel memoir

Journeys Beyond and Within…

is here!

In my usual self-deprecating, vivid narrative style (that you love so much, ahem), I have put out my most unusual and challenging adventures. Embarrassingly honest, witty, and introspective, the book will entertain you if not also inspire you to travel, rediscover home, and leap over the boundaries.

Grab your copy now!

Ebook, paperback, and hardcase available on Amazon worldwide. Make some ice tea and get reading 🙂

*****

*****

Want similar inspiration and ideas in your inbox? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter "Looking Inwards"!