How to Edit a Memoir

I am assuming you have the first draft of your memoir. I have written about writing the first draft of my travel memoir, sharing my experience. The main thing one needs to do to write the first draft is to write it. To not edit it, to not overthink it, and to not worry about editing either.

The first draft is the first step. Write it all out without stopping for commas, calls, or cramps. Say everything you ever wanted to say: on topic or random ramble. Those thoughts won’t let your gut settle unless you spit them out.

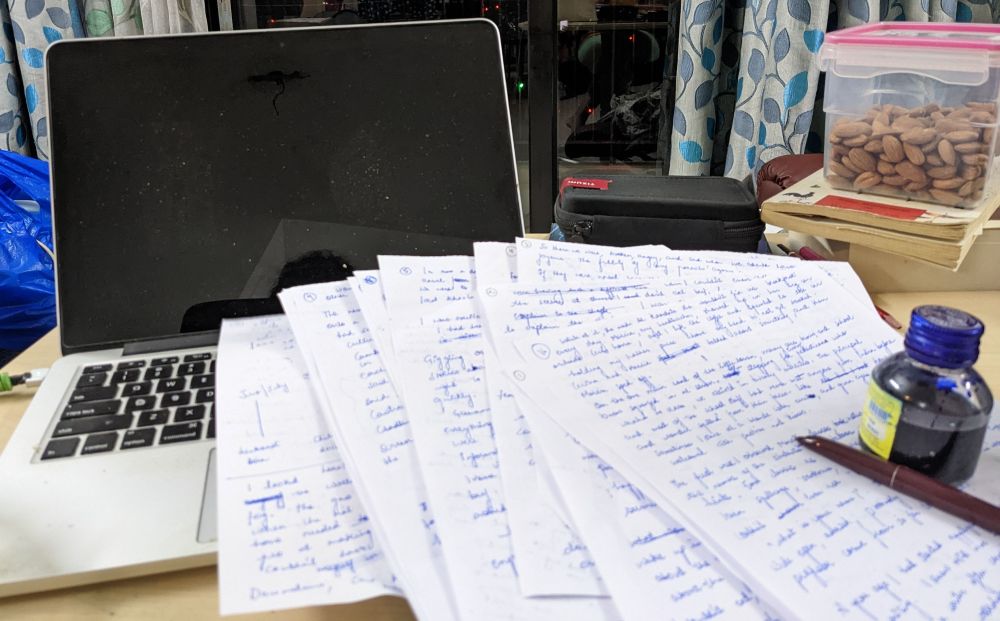

After the first draft, you can follow these tips on how to edit a memoir. While writing my first book, Journeys Beyond and Within…, I had many editing notes on my Mac. Each of these notes carried various editing tips. While one note had a list of books I was reading on how to write a book, another one held the highlights collected from one of those books. A note was titled: Editing Tips for the book as a whole, and the below tips were under the heading: Writing Tips.

More than writing tips, these are editing tips. I had written an extensive first draft. My editor had told me that cutting out later is easier than writing it down later. I wrote more than needed. First, I scribbled a 65000-word draft, from which I sieved tentative chapter titles, and then I started expanding all those individual stories. Now again, following her advice, I wrote each chapter in excruciating detail, or so I thought. Later on a website for writers where writers critique each other’s work, I was told that I needed to sketch my characters better.

That early feedback helped me expand the story, make the people real, and cut it down. The second thing that helped me edit the memoir is the tips below that I collected from the internet, books, and everything that came across me, much like a bird gathers feathers, cotton, and twigs on every flight, everything a possible raw material for her nest.

I read these editing tips every day as soon as I sat down at my desk, and sometimes while writing too. I perused them infinite times, ensuring that the narrative was taut (my editor noted my usage of this word) and that every word had gone under my scrutinizing eye.

Every word in your memoir should have a purpose. If you follow these 39 tips diligently, they will swallow every extra word. These editing methods, as the title says, are best suited for a memoir. A lot of them will apply to a novel, too. But not all, and then it won’t be an exhaustive list for fiction. For fiction, take what is of use and add more.

Okay, onto the work now.

How to Edit a Nonfiction Book: My Precious Hand-Collected 39 Writing Tips I Followed to Edit My 5-Star Rated Travel Memoir

1. The lesson or incident could be very simple — something that impacted you.

I had read that travel narratives should have a lesson, that the outward journey or voyage should change something within the traveler. I had written much on how travel changes us and what travel showed me about the world and myself, but I hadn’t thought of every trip as a lesson-imparting granny.

I had to carefully think about what I might have learned on each adventure. Here I was telling myself that I didn’t have to come up with a sophisticated lesson. It could be simple, as simple as that we don’t have to consider ourselves lesser than others.

Adapt this tip as per your nonfiction genre. The point you are trying to make or show could be simple and still significant, as it is important to you.

2. Don’t be boastful. Don’t try to set yourself apart from the rest —be veracious.

You were there, and you did what you had to do — like anyone would. That makes the writing relatable. People can see themselves doing things you did . Otherwise, you might have the pleasure of being the hero or representing yourself as a hero, but readers would hate you. What would be the purpose of writing then— vanity? Self-gloating?

This editing tip is self-explanatory and applicable to all nonfiction. Be humble. Share your experience, talk to the people, rather than talking at them, and don’t try to show how great you are. Tell things as they happened.

3. “No self-dramatizing, no desire to reinvent herself as someone else, and certainly no desire to see travel as a means of escape from the reality of home.”

This line is from the book The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing, edited by Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs. Susan Bassnett complimented the travel letters of Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, whose writing I haven’t read, yet. But the lines stuck with me.

I mainly focused on the first clause of this instruction. Because surely I wanted to change for the good, and surely at times travel became a great relief, especially when I was under too much marriage pressure at home in India. I don’t think I was wrong in wanting to get away for a while or be anyone on a day on the beach or in the forest where no one knew me.

No self-dramatizing, though. No drama. No hyping the troubles or the fact that I was traveling alone for months. Just stating it all as it was.

4. Focus on one theme per story. Build everything towards that. More than that, and people would be lost.

A good old writing tip, especially for nonfiction and memoirs. Maybe you want to talk about your mother’s garden, but you are also writing about her issues with your father. Or you are writing about the garden, but you can’t stop talking about the delicious dishes that came out of her kitchen. Now look at it like this. Only keep whatever you can put in one pot to make one main meal. No side dishes, salads, or entrees. You don’t want the reader full before he reaches your main story.

For my story on being alone in the honeymoon hills of Kerala, I focused on my interaction with the driver. I only included those conversations and landscape details that were relevant to that interaction.

Choose small. Think of the theme as a beehive. Everything you tell should fit into those honeycomb cells.

If you are curious, find the fourth chapter of my book.

One theme per essay, per analysis, per How to.

5. Clean, clear, concise, word-by-word, connected writing.

I have always admired the seamless writing of writers I love. Each word leads to the next, and each sentence is just a predecessor to what is to come. I enjoyed those stories the most that didn’t let me wander. I was hooked. I wasn’t questioning any data, dialogue, or situation. When I reached a phrase, I had everything I needed to know to be there, and I read with full attention. No garble words, no stuttering, no doubts, no repetitions. And this tight narrative is what I focused on creating in Journeys, too.

Applicable for all kinds of nonfiction. Of course, also for fiction, though it might not be so obvious always. (Linked are some of my best fiction reads.)

6. Find the Universal Truth of the Story

I read somewhere that you tell a story for a reason. You write when something within you wants to come undone.

I think my travel to Europe mainly reminded me how I considered myself inferior, and also taught me that I didn’t have to. I didn’t know this as I began writing the Europe travelogue, though. The intention became clear as I edited the narrative. I was cutting out incidents and conversations to make space for a sole feeling: How liberated I felt after visiting Europe.

Your universal truth is why you write in the first place. Don’t worry, for it will become clear as you keep working on the draft. Readers will connect with your universal truth because they will have their own version of it.

Applicable for all genres.

7. The beginning should be about what the essay is about

The beginning is the most important part of any writing: fiction or nonfiction.

I write simply, and so my beginnings are obvious, at least as much as I can make them.

The first sentence in my Chile travel essay was: Within a hundred days, night became day, and day became night.

I wanted to show how out of place I was, and that was mostly the theme of the narrative, with a slight twist, though.

Begin your beginnings well. Grab the reader.

8. If someone zooms into a paragraph of your book — as you do in others’, understanding their every phrase, every line —they should find meaning in all of it. Nothing superficial, preachy, boring, repeated, or virtuous.

The best of the writers had shown me this. No matter how long Gora or Swann’s Way was, every sentence was crucial and written with equal care.

I didn’t want to lose my vision in the middle of the story. No straying. No daydreaming. We might be writing thousands of paragraphs and hundreds of pages, but every word is important. Just because the book is long does’t mean we can blabber in between. The reader would go through each word, and each word should earn its place.

Equal care for your nonfiction and fiction.

9. Only have what you really felt

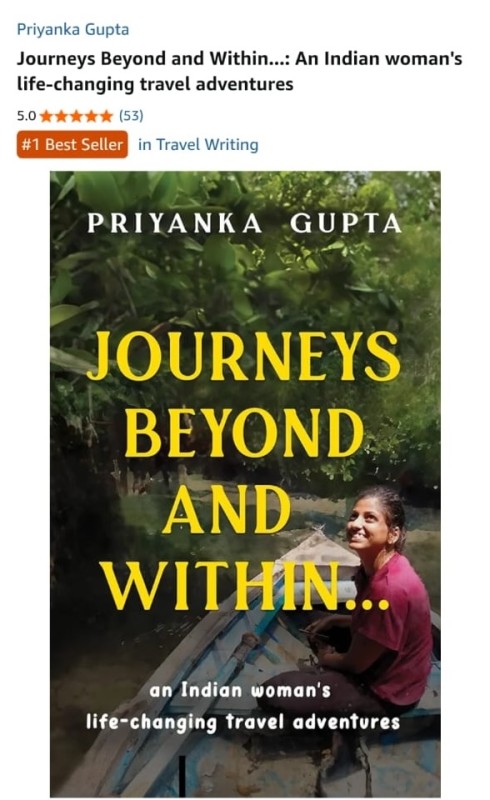

My travel memoir, Journeys Beyond and Within…, is often praised as extremely honest, candid, and true to the soul. Readers say that with my book in their hands, they feel as if a friend is sitting next to them, telling them a story over chai.

Readers feel that my stories are honest because they are. I wrote only those stories and those aspects of them that I was sure of. Was I really that clueless about the mountain on my first Himalayan hike? Was I thinking about how different that sandy shore of Lake Titicaca was from home beaches while I was on the shore? I kept what I was confident about and cut the rest.

Readers can sense the honesty through the pages like a cat can smell fish from miles away.

True for all nonfiction genres.

10. Path to peace of mind. Something inside me needs to leave.

This is similar to point five, the universal theme.

You tell a story because you want to tell it. It cannot stay within. After writing my memoir, I have made sense of all those adventures. I have accepted them, with their good and bad, and understood what they mean to me.

11. Every great story has a great metaphor working for it.

I recommend May Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude from my collection of books about writing books. The journal’s chapters that impacted me most were those in which a physical change unfolding in front of her became a metaphor for her inner journey. I once wrote in my newsletter that the browning and yellowing of trees beyond my guesthouse window was a sign for me to leave, too.

In my travel memoir, I had to look for physical changes or movements that reflected a change within me. The physical progress can be as simple as accepting a glass of wine or as dramatic as crossing seven seas to find parts of yourself you didn’t recognize before.

Once we make sense of our stories, our readers understand them, too.

12. What was the external change or scene that you could visualize internally? Mirror reflection. That’s the universal there. Find that in every story. You have to keep holding that one thread, unravelling it, ignoring the hundred others.

This editing method is similar to the universal theme and the external physical mirror. I kept repetitions of it to have it on my fingertips.

13. From one thought to another seamlessly, as if that is the only thing you have to care about right now.

The story unrolls like a movie. You don’t think: And then what, how did this happen, or what happened to that guy? Have the reader by the throat. She only cares about what you want her to care about. That can be achieved through tight word-by-word narration, sentences unfolding into one another like a breath taken in and breathed out.

14. “He (Van Gogh) was willing to sacrifice a naive realism in order to achieve realism of a deeper sort, like a poet who, though less factual than a journalist in describing an event, may nevertheless reveal truths about it that find no place in the other’s literal grid.” Alain De Botton, as said in The Art of Travel, another book that I reread while writing mine.

In journalistic nonfiction, you might have to be exact. Even then, your interpretation of the events is your unique view. Botton reminded me that great writing feels true, speaks the obvious, and yet it is its own version of the truth. Of course, Van Gogh inspires me to keep going.

15. Every scene should be complete in itself with a beginning, middle, and end.

I read this in a book on tips for editing books. This was new to me, honestly. I often thought that we leave scenes incomplete. Imagine a fight where a person storms off. Or a station where the train leaves, but the passenger couldn’t climb.

No matter how they look, all scenes are complete. Maybe the one who stormed out is now standing behind the door, rethinking her decision. The passenger is already turning around to run to the station master to ask for options. Writers have to create scenes that satisfy the reader.

Have a beginning, a build-up or a middle, and an end to every scene. Especially important for creative nonfiction.

16. Precise sentences bereft of redundant words.

No actually. No very. If a sentence means the same without a word, delete that word.

Or rewrite.

I was expecting him to show up.

He will show up. (Better)

Actually, I would have loved to have you there.

You should have been there. (Better)

17. Clean and simple writing.

This is similar to the fourth point. A reminder for me to keep it simple.

Applicable for all nonfiction categories. (Here are some of my best nonfiction reads.)

18. You should be able to imagine it as a movie

A video is seamless. A couple of days after reading the Woman in the Cabin, a haunting but entertaining book, I couldn’t tell if I had seen a movie or read the book. Sometimes I still get confused (like right now). I read the book, but it was so visual and so good that I felt I had seen a movie.

Not that movies are better than books. The other way around. In movies, the scene already contains everything. You are supposed to take it all in through your visual senses. In books, you construct the world word by word, slowly finding yourself inside it.

I say you should see a book as a movie because a movie is seamless. It flows. The writing should flow too.

More for creative nonfiction but also for how-to or journalistic essays, recipes, interviews, and research papers. The whole thing should be stitched together tightly.

19. What is the question you are answering?

If you are answering one.

At times, my question was my theme. What was I trying to achieve by telling that story? Was I trying to find more of me? Was the present me not enough? Was I brave?

You should be clear about what you want from your nonfiction. It could be something simple.

20. If something confuses you, don’t leave it like that. Solve the problem. Be precise.

Sometimes I was unsure of what I wanted to say or how I felt. I would keep lingering around the paragraph, not changing it or cutting it, just reading over it. Then one afternoon, as I skimmed that part, I realized that the reader would probably turn the whole page over.

A writer can’t afford to bore or confuse a reader.

If you are confused, the writing would be unclear, and the readers would be confused too. Solve every problem. It’s your job. (Who said it would be easy?)

21. Every chapter should have one single purpose. Bring every line to build up to that purpose.

A repetition of the matter of the theme, said in a different way.

22. The narrative should be like a river. No obstructions. It is my job to make it that way.

23. Lessons will come along the way.

You understand why you are writing while you are writing. Unless it is a research piece or a commissioned interview, where you know from the beginning. Even then, a theme would want to settle in and will do so with time.

24. Word by word

I would write it on your t-shirt if I could.

25. Edit one story at a time. Each story is important. No meandering.

I had thirty-five stories in my first draft. Thirty six, probably. (The book has ten chapters, and I send a special gift story to interested readers separately.) I had to edit one story at a time, or I would have been writing my memoir till today.

When I was editing a chapter, I forgot about the rest until I had to tie the whole book together.

26. Ask Yourself — “Bad literature presents the reader with conventional stereotypes and encourages him to assume a role which, in the very nature of things, must be different from what he really is. Good literature presents the reader with the results of an honest investigation into what is, and so encourages him to break out of the role he happens to be playing and to discover for himself the realities of perception, thought, and feeling that lie behind his assumed mask and have been eclipsed by it.” Aldous Huxley, as he wrote in the essay, Literature and Modern Life. I discovered the essay in the book, Best of Indian Literature 1957-2007 Volume 1 Book 1.

I was enthralled by Huxley’s essay, forgetting to breathe. I read it many times over and copied this paragraph into my editing tips. This is all I ever wanted to hear and needed to hear. All writers are researchers, investigators, and scientists. First, we understand, and then we share what we know, hoping others would figure it out for themselves too. That’s all we do.

27. Don’t leave anything just because you wrote it.

Is that beautiful paragraph you wrote on that moony morning crucial to the story? You love it? Is it crucial to the story? What did you say? No? Did I hear it right? Cut it out.

28. Every word should be strong, visual, and impactful, like poetry. Be poetic, vehement, and direct like Neruda.

Your writing is a trunk call. Every second and every word matters. Now edit.

29. Think about what you would have wanted to know from someone who had lived your kind of life. Answer those questions, and tell those stories.

Nonfiction is about sharing our experience. People who are interested in our topic might read our work.

In my travel memoir, I didn’t write down the most impressive stories. Nothing of the toughest hike or the coolest place, though I was tempted to. I penned down some of my hardest adventures, most embarrassing incidents, and things that had made me pull my hair. Because those were the most felt and strongest memories. I showed the readers how I struggled with something as simple as driving a scooter on a steep hill. So they could relate to me and understand how challenging a simple task might seem in a new destination, perhaps thinking of some of their own past adventures.

I focused on stories that answered questions such as: How do you work on the go? Weren’t you scared? How did you know you would do it? So what did your parents say?

This editing method is relevant for all nonfiction genres. Creative nonfiction, research or academic, and also how to.

30. Writing is .001+.001=0.002.

Consider everyone a novice (even if they are experts). Explain as you would explain to a child (this simplifies the whole thing in your head, too). Tell the basics first.

31. The end part of all that learning need not be at the end of the essay. You can sprinkle it throughout the story. End with a movement or profound thought, not a lesson.

In the first drafts, I wrote multiple pages of observations and lessons at the end of each travelogue. The stories were active and a lot of fun, ending with the long lesson.

The books I was reading didn’t necessarily have learnings at the end. The critiques on the writing website said that they might not read the long lesson at the end of a chapter. That I could sprinkle it about and cut short at the end.

Won’t the narrative feel shallow then? How will I share what I had learned, or unlearned?

In the end, I decided to let the learning grow through the memoir rather than delivering it as a gunshot at the end. I, as a reader, also wanted a shorter lesson. Good travel writing should show me the growth, not spoonfeed me.

Think of yourself as a reader. What would you like?

32. Read Aldous Huxley’s essay, Literature and Modern Life, again.

33. Keep only the things that move the piece forward or tell something about a character.

This is popular for fiction, but is relevant for nonfiction too.

34. What happened or what was happening with my family and how I felt should not be in big paragraphs but dissolved throughout the stories, like salt.

Shorten the paragraphs one sentence, or one word, at a time. Then they won’t sit like the big stones as they do now, but you would have squeezed them so much that they’d fit in the nooks and crevices of your life (in which spiders, insects, and snakes live). The foundation is built around them.

As these were my personal tips on editing, they were more specific to my travel memoir. But this idea could apply to something in your work as well? What are some things you hate to talk about but have to talk about? What are the undercurrents of your life? You, too, might want to soak your paper in them.

35. How to use flashbacks?

Cheryl Strayed (in her book, Wild) dusted off past incidents and people whenever the current narrative needed them.

We don’t have to tell everything as it happened. We can always bring in something from the past at a relevant juncture.

36. Everyone needs someone to tell them that their life is okay. That human beings are flawed, they haven’t always harmed us intentionally, even our parents couldn’t protect us all the time, they didn’t know, and we all share the pains of this world, and that nothing is so great or so bad in anyone’s life. This is how it was supposed to be.

The readers will read your stories, essays, and interviews, and calm down. Countless readers told me that they were happy to know that someone else was going through something similar.

Be honest, make your pains laughable, and give others a good time.

37. Do you want to write things that might hurt your friends or family?

Write whatever you want to write, but without judgment or anger. Forgive and move forward. No one wants to read a rant or an angry monologue, and your book shouldn’t be the outlet you need. You are supposed to make sense of the incident so others can draw from it too. That’s your only job. (Virginia Woolf talks about how writers need to process everything without taking it personally.)

38. I am going to call a stick for a stick everywhere it appears. This is what I have to remember.

Well, what can you do?

As Anne Lamott said, “If people wanted you to write good about them, they should have behaved better.”

39. Writers always talk of the most obvious things that people are afraid to say.

Good luck!

What is your most effective tip to edit nonfiction?

MY FIRST BOOK

Journeys Beyond and Within...

IS HERE!

In my vivid narrative style (that readers love, ahem), I have told my most incredible adventures, including a nine-month solo trip to South America. In the candid book, the scoldings I got from home for not settling down and the fears and obstacles I faced, along with my career experiments, are laid bare. Witty and introspective, the memoir will make you laugh and inspire you to travel, rediscover home, and leap over the boundaries.

Sikkim Express: "Simple, free-flowing, but immensely evocative."

The Telegraph Online: "An introspective as well as an adventurous read."

Grab your copy now!

The memoir is available globally. Search for the title on your country's Amazon.

Or, read a chapter first. Claim your completely free First Chapter here.

Want similar inspiration and ideas in your inbox? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, Looking Inwards.